The rituals honoring Centeotl, the Maize God, caught my attention with their profound reverence for life's cyclical nature. These ceremonies, overseen by priests, transcended mere crop yields; they symbolized life's perpetual renewal. Festivals marking planting and harvesting seasons became vibrant displays of communal appreciation and optimism. Centeotl's youthful depiction, adorned with maize, underscored this deity's intrinsic tie to agriculture and sustenance. What intrigued me most was how these practices mirrored other agricultural deities, revealing universal spiritual themes centered around humanity's reliance on nature's bounty. But why did maize hold such a sacred role?

Historical Significance

In the Aztec civilization, Centeotl's worship played a pivotal role, symbolizing life's cycles through agriculture. As the deity of maize, Centeotl was essential for daily life and farming prosperity. Maize was a divine gift, and Centeotl controlled crop fates. His influence transcended sustenance, intertwining with Aztec spirituality and community.

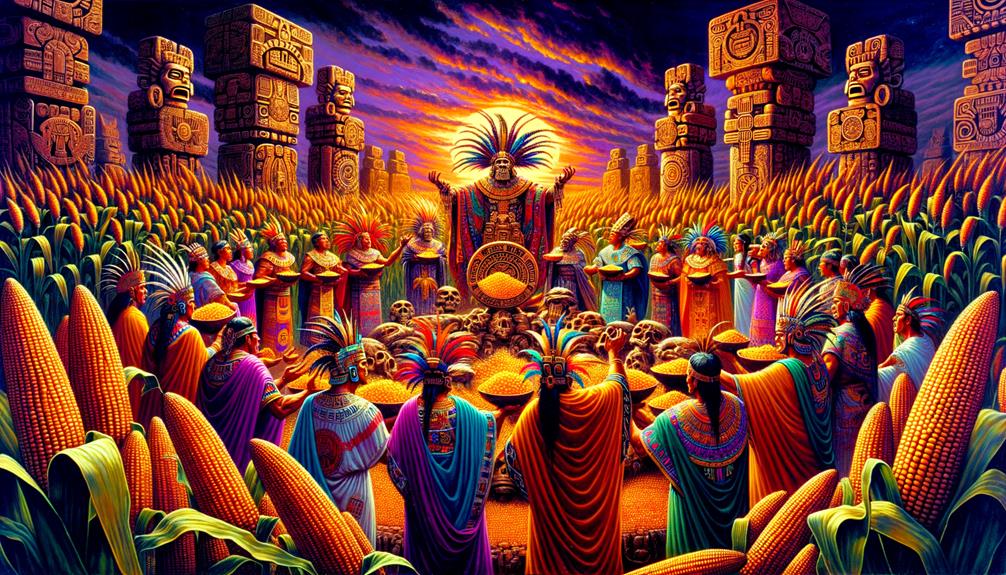

Honoring Centeotl involved elaborate rituals and ceremonies, highlighting his significance. Priests oversaw planting and harvesting, interpreting nature's signs for ideal timing and bountiful yields. The devotion showed to Centeotl directly impacted agricultural abundance, reflecting the profound reverence the Aztecs held.

Sacrifices expressed gratitude and ensured prosperity, not just appeasement. This cyclical veneration symbolized an eternal bond between Centeotl, the earth, and the people, underscoring his profound historical importance.

Rituals and Sacrifices

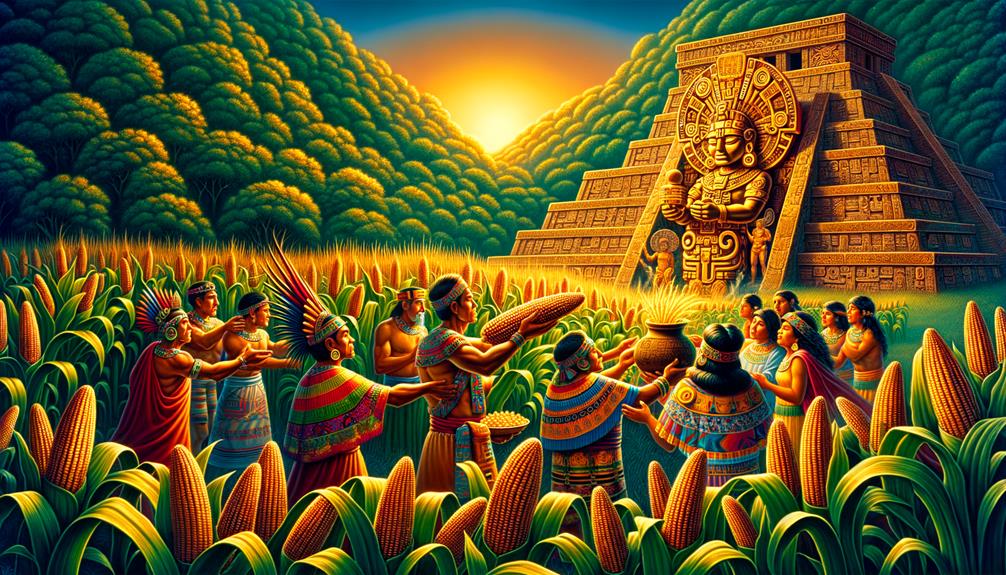

In Aztec culture, rituals and sacrifices dedicated to Centeotl, the maize god, carried immense significance. These practices were more than just customs – they linked the community's sustenance to divine favor. Ritual dances in maize fields expressed gratitude, aiming to ensure continued prosperity. Priests interpreted natural signs to determine optimal planting times, combining divine wisdom with practical agriculture.

When maize fields failed, and famine loomed, the rituals took a solemn turn. Volunteers, often priests themselves, sacrificed their lives to appease Centeotl. These human sacrifices were profound acts of devotion, made to restore fertility to the land. The volunteers believed Centeotl would embrace them in bliss before death, transforming their ultimate sacrifice into a sacred duty.

These rituals and sacrifices reflected a deep cyclical understanding of life. They highlighted the belief that prosperity, famine, life, and death were intricately tied together in the sacred dance of existence.

Festivals and Celebrations

Centeotl festivals extend beyond rituals into grand celebrations marking planting and harvesting seasons, reflecting the community's gratitude and hopes for agricultural bounty. During these times, priests interpret nature signs, guiding planting periods to align community efforts with divine favor.

These vibrant affairs feature intricate rituals and dances, each movement and chant symbolically invoking blessings for a bountiful harvest. More than acts of devotion, they foster unity and shared purpose.

At their core lie sacrifices offered by volunteers, often priests themselves, during famines. These sacrifices plead for Centeotl's mercy and intervention. The celebrations mirror planting and harvesting cycles, representing the constant renewal and sustenance provided by the maize god.

Through these festivals, the community expresses its interconnectedness with the divine, nature, and life's cycles, ensuring Centeotl's grace continues to nourish and sustain them.

Role of Priests

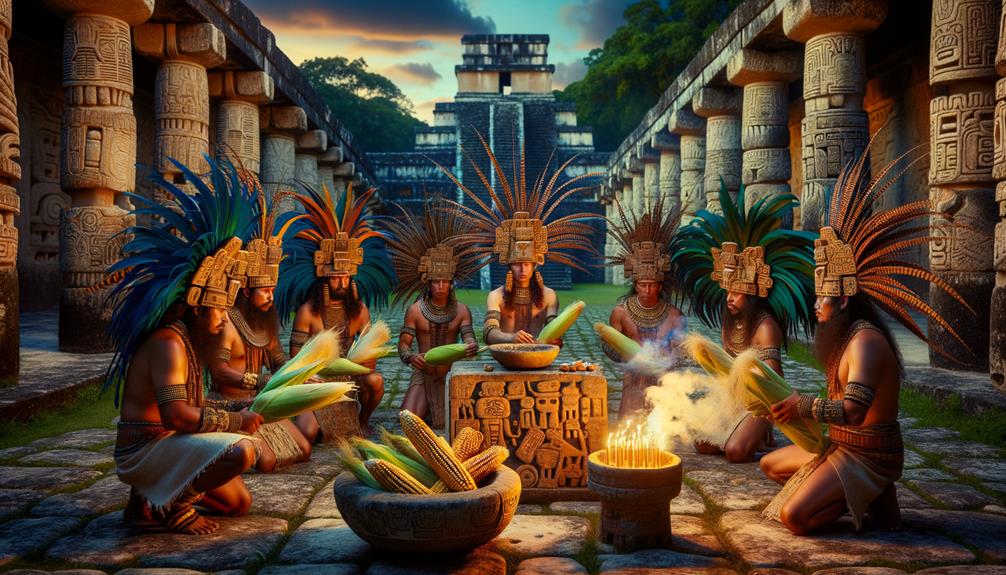

Priests of Centeotl, the maize god, hold tremendous sway over the agricultural cycles vital to the Aztec people's subsistence. They interpret natural signs to determine the optimal sowing periods, ensuring Centeotl's favor for a bountiful harvest. This sacred responsibility places them at the heart of community survival, as their interpretations directly impact crop yields.

To honor Centeotl and secure abundant harvests, these priests perform intricate rituals and ceremonies. These aren't mere formalities but acts of devotion aimed at appeasing the maize deity. During times of scarcity like famine, the rites may involve offerings and, in extreme cases, voluntary sacrifices by the priests themselves, reaffirming their commitment to maintaining divine-human balance.

These priests not only oversee planting and harvesting but embody the spiritual essence of the agricultural cycle itself. Their guidance and rituals ensure the community remains in Centeotl's good graces, securing the crucial food crops needed for survival. As such, they serve as both earthly stewards and spiritual guardians of agricultural prosperity.

Symbolism and Depictions

Centeotl, the Aztec maize god, was depicted as a youthful man adorned with a maize headdress and golden skin, a vivid representation of fertility and abundance central to Aztec beliefs. His portrayal, with maize sprouts and ears emerging from his head, highlighted his deep connection to agriculture and the life-sustaining qualities of maize. Radiant golden skin symbolized the nourishment from the sun and the prosperity brought by a bountiful harvest.

The slightly effeminate features emphasized Centeotl's nurturing, life-giving role. Surrounding him were maize plants, potent symbols of the cyclical nature of life, reinforcing his pivotal role in ensuring plentiful harvests. While other cultures had agricultural deities embodying growth and sustenance, Centeotl's unique youthful visage with golden skin positioned him as central to both spiritual and practical aspects of Aztec society.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Was Centeotl Worshipped?

When it came to honoring deities like Centeotl, the people performed rituals and sacrifices, scrutinizing nature for signs. Their actions aimed to encourage fertility and abundant harvests, reflecting the age-old human reliance on divine favor for agricultural success and survival. This straightforward approach highlighted the deep reverence held for the sacred forces governing the crops that sustained their existence.

What Was Maize Deity the God Of?

The maize deity represented the cycle of life, embodying nature's abundance and humankind's reliance on fertile crops. This archetype reflects agricultural societies' reverence for bountiful harvests ensuring survival. Through comparative religion, we understand these deities' universal symbolism across cultures dependent on successful cultivation.

Who Is the Aztec Corn Husk God?

Nearly 80% of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations depended on corn as their dietary staple. The Aztecs revered Centeotl, their maize goddess, representing fertility and nourishment – mirroring universal veneration of agricultural deities across global faiths. Farming communities built symbolic connections between bountiful harvests and divine forces, shaping religious perspectives around food sources essential for survival.

Why Did the Aztec Worship Corn?

Corn held immense cultural significance for the Aztecs – it nourished their bodies and souls. Its growth cycles reflected the rhythms of human existence, representing fertility and renewal. This ever-abundant staple naturally became central to their spirituality and survival. The Aztecs found deep meaning in corn's phases, viewing it as emblematic of the perpetual cycle of life.

What Gods Did Aztecs Worship?

I delved into Aztec worship and uncovered deities like Huitzilopochtli, their war god, and Tlaloc, the rain deity. Their pantheon centered on universal themes like creation, destruction, and fertility – elements key to grasping their complex, agriculture-driven society.

The Aztec gods played pivotal roles within their culture. Huitzilopochtli, as the war god, exemplified the valor and sacrifices required for conquering rival peoples. Tlaloc's status as rain deity highlighted the reliance on sufficient rainfall for successful crop yields. Other prominent figures included Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent representing wind and knowledge. Together, this robust theology illuminated their worldview and day-to-day existence.